Growing Up as a Tomboy in Thailand

We understood that wearing clothes of the opposite sex meant you were a kathoey

Amanda Kovattana is the author of The Unexpected Penis: Conversations on the Gender Trail - a beginners guide to the gender wars and how we got here, written from the perspective of an outsider with third gender culture knowledge.

I was eight, running full tilt through our house in Bangkok, when my aunt stopped me, put a hand on my shoulder and said:

“You have the spirit of a boy.”

Those words filled me with joy.

I felt seen and acknowledged.

Her words gave me space to be my full tomboy self and off I ran again, even wilder and noisier than before.

In the context of our Thai reincarnation culture, she also meant I had innate wisdom from a previous life as a man. I understood that my family would help me adjust to my new body so that I could learn what I had come to this life to learn, and that they would not be too hard on me for not being a girly girl or wanting to wear dresses.

This is the opposite of what trans ideology tells kids.

Thailand was still a pre-industrialized country back then. We bought children’s clothes in the market sewn by local seamstresses.

We understood that wearing the clothes of the opposite sex meant that you were a kathoey.

Boys especially wanted to avoid this third gender designation of a cross-dressing individual, but I didn’t mind being labeled a kathoey.

It was just the way I was.

My English mother honored my request for pants with pockets. This was 1966, still a venerable time for tomboys and she taught me the word. She had been a tomboy, too, playing in the rubble in a bombed out London.

The pants she found for me were dark blue with white topstitching and the letter ‘A’ embroidered on a tiny pocket on top of a pocket.

She got me a sailor dress with pockets, too.

In my family it was understood that what you wore within the walls of our compound was your choice, even if you wanted to wear pajamas all day. But if you were going out you were representing the family and our collective identity, so the clothes you wore outside represented your class status and were not necessarily your individual preferences.

One day a relative who was a seamstress stopped by with a gift for me. She had made me a shirt with a collar and buttons down the front, just like a boy’s shirt, in a Thai cotton print in lavender with matching solid purple shorts. This was a very special outfit that honored my “boy spirit,” and it was so nice that I was allowed to wear it on a weekend away with my grandmother to a festival at a beach town.

Nobody mentioned anything about it being a boy’s outfit.

At the age of ten we immigrated to California, where I was allowed to dress in my tomboy clothes whenever I wanted, except for my private school uniform. In California, when I saw how much more status boys had, and how much more was offered to them, I wanted to be a boy, too.

Also, I wanted a paper route, but it would be a few more years before girls were granted this iconic American job.

Occasionally, in high school, we had free dress days and I would sweat it trying to come up with an outfit that wouldn’t betray my boyish preferences too much; I was beginning to realize that I was likely a lesbian, and on these days I sometimes wore a tan corduroy Levi’s jacket with tan high-waisted pants, as was the fashion at the time.

Then in my junior year the school put on the mostly boys play Oliver, and I won the part of the Artful Dodger.

What a great vehicle for a blossoming butch lesbian!

I fully embraced the part, wore my top hat and tailcoat with pride and put on a cockney accent.

When I returned to Thailand as an adult, I made the acquaintance of a butch lesbian and learned that we were called Toms, short for tomboy, and that femme counterparts were called Dees, short for lady. In a collective society these butch/femme pairings were common because people liked to know what role to play in courting a partner.

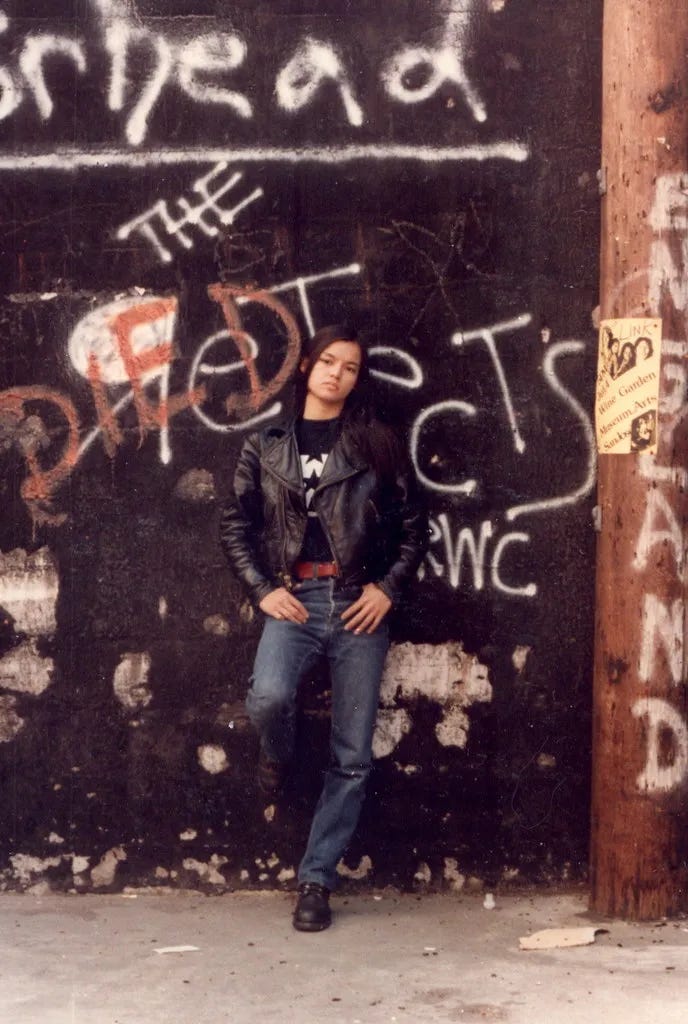

My friend had the short haircut expected of a butch, while I kept my hair long because I thought long hair made me look “more Asian.” It was important to me to claim my Asian heritage as a biracial woman, but I also didn’t want to look like a man, and short hair on an Asian woman was too easily mistaken for a boy for my taste.

In Thailand people understood me as a member of Thai society who was gay. While in the States, Americans could not see past my Asian girl looks and I became more of an Emma Peel figure, feminist icon from The Avengers. This duality was liberating and suited me perfectly.

Today, I continue to enjoy designing clothes for my gender bending ways.

For me as an adult, the whole point of being a tomboy is to provide an alternative presentation of a woman, not to “become” a man.

For more gender non-conforming voices, read

popular story of growing up in Connecticut:I Was a Girl Who Wanted to Be a Boy...

“I am not wearing dresses ever again!” I proclaimed at age seven.