In this post, former public school teacher Jordana Kagan joins me to advocate for K-12 vocational education. She share ans her insight for guiding interested students toward skilled trades.

The pandemic lockdowns and Zoom “instruction” opened the eyes of many parents to the realities of what was happening in our nation’s public schools. We began to witness educators teaching young children information about their bodies that went against reason and biological truth. Then, there was the growing political activism seen in high school and higher education institutions that was encouraged by teachers and professors.

Even worse, led by teachers’ unions, there was a growing effort to wedge distance between students and their parents and families. Some school districts and private schools created policies that permitted school staff to withhold mental and physical health information from parents about their children.

The frustrations of school closures, social isolation, the growing prevalence of mental health problems in adolescents, and the poor performance of students in math and literacy compounded parental worries.

Our goal as a society is to produce healthy, robust, happy citizens who excel at their craft with confidence, a sense of independence, and agency. However, many parents realized for the first time that our nation’s public schools were not helping our children reach these goals.

This left parents wondering about other options for educating their children.

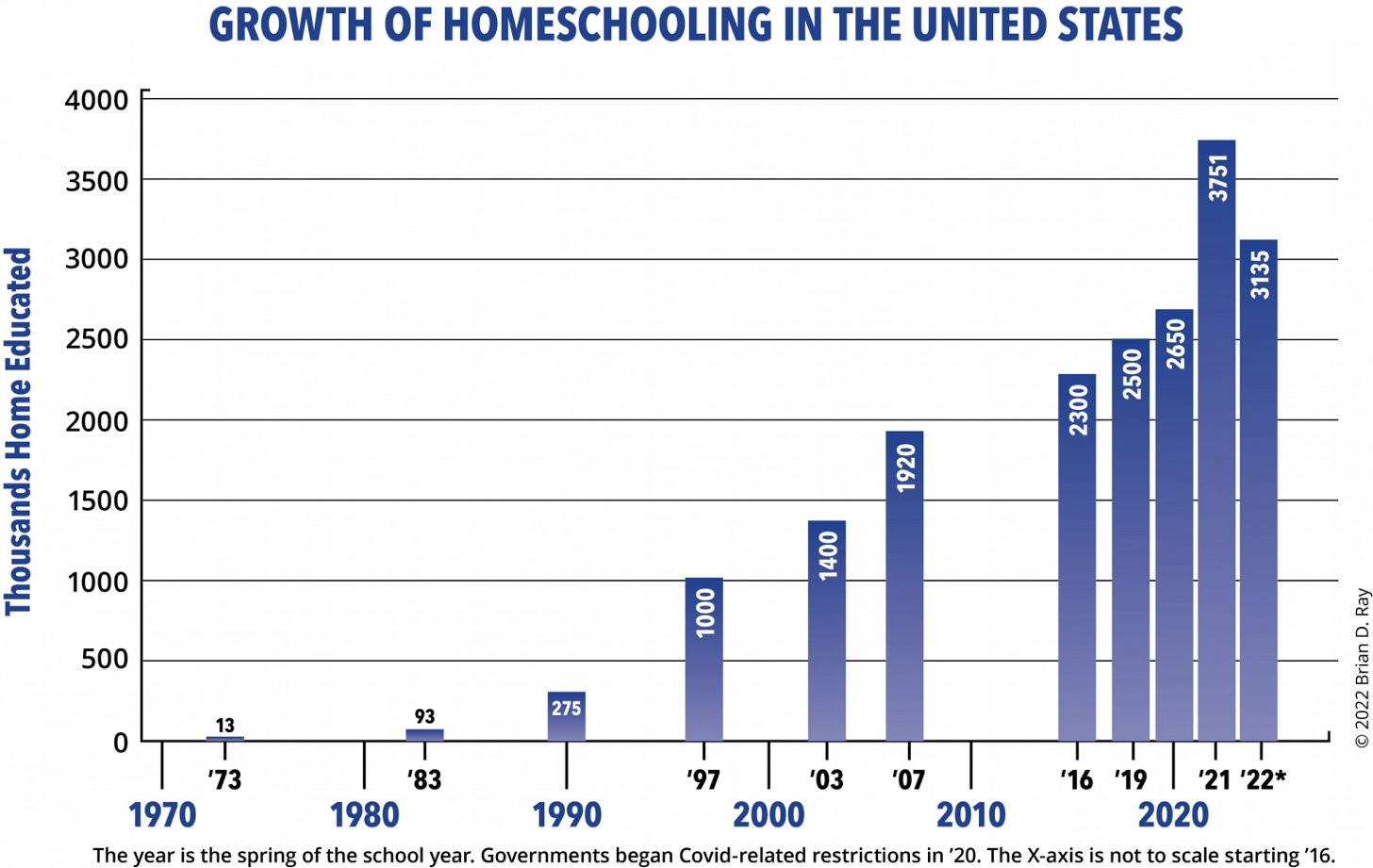

Traditional public schools began to see student enrollment decline. Rates of homeschooling tripled nationwide from mid-May 2019 to 2021 and doubled from March 2020 to March 2021, and there was an increase in demand for school choice legislation.

Also, student and parent interest in skilled trade educational options began to grow even before the pandemic as parents saw the high costs of college and university education lead to insurmountable student debt.

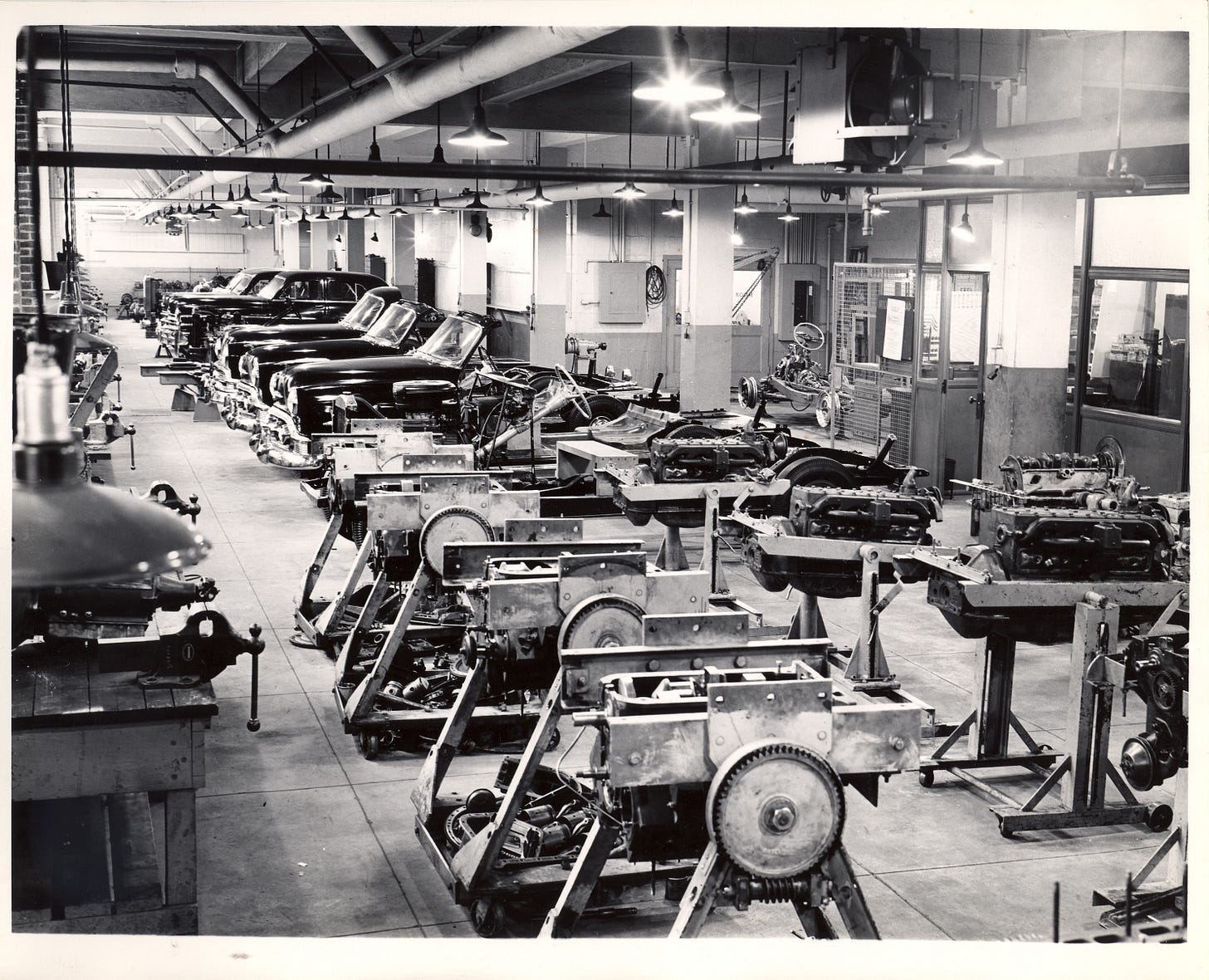

Skilled trades like auto mechanics, carpentry, and welding were once part of K-12 education but were phased out in the 1980s. Though many factors were involved, skilled vocations and trades were given a bad rap by educators and used as dumping grounds for underperforming students. Political pressure to improve academic performance also took priority.

But not every kid wants to attend college, nor does he need a college degree to excel.

A quality vocational education program can provide young people with an excellent education and instill invaluable skills, giving way to competency and independence. A teenager can become a craftsman—a professional with an honorable trade, a sense of pride, and the confidence to pursue his or her dreams and entrepreneurial endeavors.

Our goal as a society is to produce healthy, robust, happy citizens who excel at their craft with confidence, a sense of independence, and agency.

But how do you steer students down a nontraditional path without making them feel inadequate? How do educators and parents have a conversation with children about the best path forward?

Steering individual students down the best path for achieving their dreams requires a growth mindset defined by consistent practice, regular self-monitoring and reflection, and mindful application of feedback over an extended period of time. This process will inevitably lead to growth and enlighten the student whether or not pursuing the goal is “for” him.

He might have the aptitude or the talent but may lack interest. Or perhaps he has the passion but isn't mature enough and needs other experiences before fully committing to the goal. Whatever the circumstances, educators and parents must be comfortable saying, “This isn't for you.”

In his book This is Marketing, author and innovator Seth Godin writes, “When we find the empathy to say, ‘I’m sorry, this isn't for you…’ then we also find the freedom to do work that matters” (101).

Steering individual students down the best path for achieving their dreams requires a growth mindset defined by consistent practice, regular self-monitoring and reflection, and mindful application of feedback over an extended period of time.

It takes honesty and courage to admit that something isn't for you. It also demonstrates an appreciation for diversity. By admitting, “This isn't for you,” with acceptance and faith—as opposed to “This isn’t for you,” with implicit judgment and deprecation—we open the doors for new opportunities better suited to a particular individual.

Interestingly, emphasis on pronouns matters in this context. Several years ago, I attended a workshop with the National Institute for the Clinical Application of Behavioral Medicine (NICABM) hosted by Ruth Buczynski. During a discussion on Working with Core Beliefs, one speaker presented the importance of self-talk as a method of self-regulation. It turns out that using non-first-person pronouns can be motivating. The second person, “you,” can activate group/social nature (”You got this!”). It also allows a person to explore his inner world (”Do you really want to do this?”).

Research from Ethan Kross and others has indicated that third-person self-talk can create distance and facilitate better decision-making (”Come on, Ethan. Get to work!”). Theoretically, “This isn’t for you” is vocalized self-talk that can help a student get on the track that is for her.)

Young students should not be told, “This isn't for you!” when they embark on their educational journey.

Firstly, every student can and should master basic literacy and numeracy skills by the time they leave middle school. Numerous technologies and techniques are available to facilitate learning to read letters and numbers—yes, math is a language—and they should be employed and deployed when students are first learning how to work with written words and mathematical equations.

Students who find it difficult to see the value of these skills need motivation and encouragement in different forms.

Educators should offer good, meaningful, and worthwhile options for instruction when possible.

Also, coupling student learning choices with positive peer pressure provides a foundation for responsible decision-making, goal-setting, time management, and self-regulation.

When young people know they will be charged with weighty responsibilities, it might prove impetus enough to engage earlier in math and reading proficiency. Letters and numbers will become consequential, creating a new culture. Students will no longer be satisfied with just passing the test. Their futures will depend not on a diploma but on skillful application and integrity.

By admitting, “This isn't for you,” with acceptance and faith—as opposed to “This isn’t for you,” with implicit judgment and deprecation—we open the doors for new opportunities better suited to a particular individual.

Secondly, young and developmentally immature students don’t have enough experience or intellectual insight to comprehend “This isn't for you.” If she hasn't had enough exposure to a given task/subject/activity, how can she determine if it is or isn’t for her?

Asking instead, “Do you want this to be for you?” and then guiding her to acquire the necessary skills would perhaps lead to better educational outcomes.

In trade schools, students learn how to do things, and then they do them. Repeated application of knowledge helps a teenager in trade school to develop problem-solving skills. As my friend Liz points out, the student becomes a creative problem-solver who taps into prior experiences and applies them in novel ways when needed—to support, fix, solve, improvise, and improve the systems in which she/he was trained.

Trade school students also learn that there are real consequences to success and failure. For example, a cosmetologist might damage the client’s skin, and a plumber might flood the house.

Offering alternative career paths through vocational training does not reduce the standard for excellence. It grants more “freedom to do work that matters.”

An additional value of trade and vocational schools is that students aren’t always restricted to an arbitrary timeline. They can pursue an extended apprenticeship if they need more practice time. In this educational paradigm, a student is ready only after demonstrating proficiency—nay, MASTERY!

The traditional educational model paces students according to set timelines and pushes students through graduation despite skill deficits.

With mentors to guide them through all means of challenge, a student in trade school can live a rewarding life arguably with more purpose and alignment than a university graduate with a degree in economics/human sexuality/art history who works part-time as a barista for lack of viable employment options in her field of study—or is denied a job as a barista because she’s overqualified.

Offering alternative career paths through vocational training does not reduce the standard for excellence. It grants more “freedom to do work that matters.”

Jordana Kagan has a theater, athletics, education, and mindfulness background. She works to strengthen the mind-body-spirit connection through authentic experiences rooted in reading fluently and thinking critically. After over twenty years as a teacher, Jordana recently left to go back to school—trade school. You can find her at https://beatsbooksbarbells.com/.