Living Through War Made Me Detransition (Part 1)

How a 25-year-old American woman who moved to the Middle East to transition to a man returned to reality

Maia Poet is an Israeli-American writer, researcher and public speaker. She began identifying as transgender at the age of 12. At 20, she moved to the Middle East - hoping to transition far away from her non-affirming parents. For four years, she lived in stealth as a man within communities of Palestinian Muslims and Orthodox Jews in Israel. Living through several regional wars helped Maia understand the impracticalities of transition. Consequently, she desisted from a trans identity, which had lasted for half of her life, and returned to the United States.

Maia now reflects on her experience of desistance, hoping to provide insight for gender distressed young people and for their parents.

Enjoy the First Chapter of Our Exclusive Series—For Free!

We are offering this initial installment for free to highlight Maia’s unique voice and extraordinary journey.

The subsequent two parts of the series will be available through a paywalled access. Your paid subscription not only grants you access to the complete series but also supports Restore Childhood’s ongoing efforts and initiatives.

We deeply appreciate your support and are committed to making a meaningful difference together.

Thank you for being a vital part of our journey.

Natalya & Dana

When I discovered the “transgender” idea on the internet in 2012, I never expected that within just a few short years, Time Magazine would declare a “Transgender tipping point.” In many ways, I witnessed the unfolding of the transgender movement from its very beginning.

As a kid, I lived entirely in my brain. I struggled to communicate my feelings, although they were so intense that sadness would often make me physically ill and when I was happy, my happiness would keep me up at night.

By middle school I had become obsessed with a rare condition called “acromegaly”, a pituitary tumor which causes the nonstop growth of the world’s tallest people. I immersed myself within my obsessions of parenting books and child psychology. Through the parenting books, I was introduced to ADHD, autism, dyslexia, hyperlexia and OCD. I was obsessed with learning as much as I could about each of those conditions.

Intellectually, I knew that gay people existed.

I was a passionate supporter of “them.”

On the other hand, I didn’t know the feelings I was experiencing were crushes.

Almost overnight, I went from being an incredibly hyperactive and cerebral child who was interested in nothing other than researching niche brain tumors, into a nervous wreck around my female classmates. I remember the inexplicable reddening of my face whenever a particular girl would smile at me, followed by dizziness and the seeming loss of all of my cognitive capabilities. The smile of a girl or the brief, accidental touch of her hand on mine while passing a stack of classroom worksheets, would transform me from a precocious poet to a stumbling idiot. My body temperature would skyrocket, followed by profuse sweating.

Had I been a neurotypical child able to pick up on social norms through peer interaction, I would have known that I was experiencing a crush. However, being the oddball junior professor, I was convinced these ‘symptoms’ were evidence I had fallen ill with a rare, deadly cancerous disease.

The onset of my sexual awakening marked a change in many of my priorities. For the first time, largely due to adults who’d started to realize that my ‘quirkiness’ was largely due to an inability to intuit unspoken social norms, I started to think about how others perceived me. A desire to belong with my peers had begun to emerge, (previously I showed significantly more interest in interacting with adults who would allow me to lecture them about whichever rare brain tumor of the week I was interested in). In my quintessentially atypical fashion, rather than finding a place within female social groups as most adolescent girls do I gravitated towards my male peers. It was comfortable to be around them because I didn’t experience these symptoms of budding romantic attraction, and I could easily maintain friendships with my male peers.

It was at this time that I first wanted to be perceived as a boy and adopt a masculine appearance. I became fully integrated with the shenanigans of middle school boys, including making whale noises whenever the teacher turned her back to the class.

While our juvenile hijinks, and our teacher’s inability to catch the culprits absolutely infuriated her, my group of male friends and I were rewarded for our obnoxious behavior by becoming instant class celebrities. We became school-wide legends, gaining special attention from some of the girls in the seventh grade. I noticed that my male classmates were getting all of the female attention, and although I was routinely elected by my classmates for the top ‘student athlete award’ (a glorified popularity contest considering my lack of participation in any organized sport), I became transparent and invisible to the girls that I was interested in as they chose my male classmates. This realization, along with the lack of reference for what female masculinity could look like, catalyzed a wave of distress which led me on a path searching for answers.

I didn’t have words to explain what was happening to me, so, like any Gen Z kid, I looked online. I had previously been exposed to the concept of a “sex change” because I grew up in a progressive, West Coast city and had seen men who attempted to pass as women. I wondered if I, as a girl, would be able to undergo a “sex change” and transform into a boy.

I went on the internet, and found my answer.

That’s the story of how in 2012, before almost anyone else had heard of ‘transgender’ I already knew everything there was to know about puberty blockers, cross sex hormones, the types of mastectomies and genital surgeries available to women who wished to pass as men.

My coming out as trans at the age of 12, occurred a decade before the availability of ample online information about trans identification as a social contagion, transition-related medical harm and detransitioners. There was also much less explicit pressure to demand affirmation, because the transgender phenomenon had not yet subsumed the zeitgeist. Therefore, when I revealed my innermost feelings to my parents regarding my desire to change sex, my parents had not yet been bombarded by ideological talking points. Naturally, they were concerned. They acted on their parental instincts and installed parental spyware on my iPad. They explained that the software would notify them of my every internet search.

The software slowed my iPad to such an extent that it became nearly unusable. As a 12 year old, I had no understanding that my parents had done this to protect me. I saw their treatment as unfair. My brother would flaunt his unbridled internet access while I was unable to continue my investigation to figure out what was so wrong with me. I felt entirely alone, because I had no meaningful friendships that I felt were trustworthy sources to confide my secrets in- and now, the source of comfort I found in the trans explanation, had been taken away, too.

My persistent desire to develop a masculine haircut and sense of style in accordance with my innermost wishes quickly became a sticking point in my personal life. As an adolescent, the best I could hope for in terms of self-discovery and stylistic experimentation was always some disappointing compromise. I wanted to wear what my male peers wore, and to have stylish haircuts like theirs, but because I was a girl, I was required to settle for at best androgynous clothes in the women’s section. My insistence on a masculine appearance, and the constant need to settle for some slightly more socially acceptable alternative made me despise my sexed body even more. After all, had I been born male, I would not have to compromise my style.

For years, I dreamt of transitioning. After my parents’ perceived ‘bad’ reaction to my initial coming out in 2012, I hid my desire to be a boy, promising myself that when I grew up, I would be transformed into the man that I so badly wanted to become.

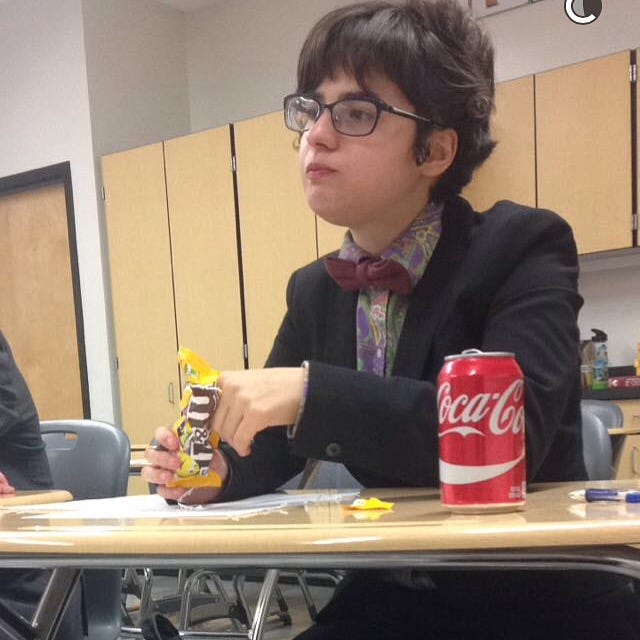

When I was 15, I decided to join the high school debate team. Speech and rhetoric were my obsessions. We would dress in suits for competitions. The boys wore ties. I wanted to wear ties, too.

I didn’t want just any old, frumpy tie borrowed from my father.

I wanted to wear bowties. As it was unacceptable for girls to wear bowties and no one would purchase one for me, I learned to sew bowties myself. Eventually I saved enough money to buy myself a nice one.

Bowties made me feel at peace with myself. And it didn't hurt that girls would pay more attention to me when I wore them.

Fast forward to 2017, my first year of college, when I realized my dream of living as a guy. I masculinized my appearance through barbershop haircuts and began experimenting with clothing styles I was never before allowed to wear.

I bought a breast binder, which I wore constantly for the next seven years, while away at college. My family grew increasingly suspicious that my persistent nonconformity was further evidence that I was in transition.

At the age of 19, I was asked if I was going by “he or they pronouns” and if I was on hormones. The “trans” subject had not been brought up for seven years by that point- since my initial coming out at the age of 12- but my appearance once again raised questions.

Upon admitting to my family that, while I had not medicalized, and I was living a transgender life, my parents stipulated that their financial support was contingent upon many new requirements. One of these requirements was that I needed to study abroad, in a country which did not have a trans-affirmative environment. I chose to study abroad in Israel, and my parents accepted that decision- probably because they didn’t realize the extent to which gender ideology had already spread within Israeli society.

The first seed of doubt was planted at the time - I was 19-years-old, when my girlfriend and I had started reading the book “Stone Butch Blues” by Leslie Feinberg. Her story resonated with me. For the first time, I had heard stories of people who were like, who described themselves and their experiences not of those as being ‘a man born in a woman’s body’ but rather as a type of lesbian experience.

The main character in the book is a butch lesbian who transitioned medically decades ago. Her choice to transition was informed by the lack of opportunities available to masculine lesbians in those days, and by her concerns for her own safety. While the transition allowed her certain social freedoms and employment opportunities, the main character discusses how the medical transition also caused her to lose her connection with the lesbian community.

Upon reading the book, I was afflicted by a realization: I had never given the chance to live as a lesbian.

Rather, from the age of 12, I had staked my entire future on the prospect of radically and permanently transforming my body so as to more closely resemble a man. The realization was both intriguing and terrifying. I was eager to explore a lesbian community in order to understand whether I would be able to find peace within myself as a lesbian, and without the need for medical interventions.

However, by 2018, no such communities existed which were known to women in my generation. So, in a bid to avoid cognitive dissonance, I stayed trans and left this thought in the back of my mind.

Then, I moved to Israel in the Summer of 2019. In Israel I was fully able to live a double life where very few people knew I was female.

Even without medicalizing, living in a traditional country where few people are aware of the concept of a ‘butch lesbian’, most people just thought I was a young guy.

While passing without medicalization was incredibly easy within that cultural context, I felt as if no one took me seriously as a man in his 20’s. I knew that in order to continue living as a man, I would need to medicalize.

Three years into fully passing as a man, I experienced a major life event which forced me to contend both with my own mortality and with the increasingly radicalizing Western Left. In May of 2021, I found myself in a suburb of Tel Aviv with my girlfriend, preparing to attend a concert when suddenly we heard a siren.

A war had started.

Within the following 11 days, we would experience thousands of missiles launched at us by the Hamas terror group governing the Gaza Strip. Every time we heard a siren, we had a mere two minutes to pack our valuables and our cats, and run to the bomb shelter.

During those long eleven days, my daily life was on pause.

I did not shower, for fear of hearing a siren and being forced to run to the bomb shelter with soap in my hair and a towel around my body. In the moments that I was not running between the bomb shelter and the apartment, I spent hours on social media.

I saw my leftist, American friends celebrating the rockets launched at Israeli civilians. Not one checked to make sure I was alive. I assumed that these friends were proponents of Hamas because they were under a spell that the terrorist group was truly a liberatory force for the Palestinian people. I tried to change my friends’ minds, through a series of detailed posts which included data from what I knew to be credible sources. While these American leftists who tweeted from their comfortable couches in California, were not swayed by my efforts, I worried for the safety of Israelis and for my Palestinian friends in Gaza.

Then, something unexpected happened as a result of my excess time spent online; the internet algorithms began to serve content which was increasingly critical of the authoritarian left. As I went down the rabbit hole of right-wing culture war content, I was suddenly exposed to gender critical opinions.

Rather than running from the cognitive dissonance, I decided to examine the narratives I learned from leftist Americans about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and later, about gender.

This moment, was not the end of my “gender journey”, as you may be compelled to believe.

This was only the beginning.

To Be Continued.

So much of your experience is reflected in my own—from the lack of understanding crushes on girls, the comfortability around boys as a result, the niche special interest deep dives, to Stone Butch Blues as a balm. Thank you so much for sharing these snippets of your journey, friend. I can’t wait to read part II.