"I can’t believe it’s been going on for so long..."

The medieval origins of the left’s antisemitism

Just days after the October 7th massacres in Israel, as antisemitism was becoming far more obviously rampant, my nine-year old asked me:

“How did antisemitism begin?”

I admitted that, even though I had attended a conservative Jewish day school from second through eighth grade, I hadn’t recalled plumbing the depths of antisemism’s roots. We certainly covered the Holocaust in great depth, but didn’t go much further back. I knew that Jews had been reviled as the killers of Jesus Christ. But, again, my knowledge was shallow and I didn’t feel like I could explain antisemitism in a satisfactory way to my daughter.

So I asked my fellow Open Schools mom and good friend Nicole Sidhu, who is a scholar of the Middle Ages, if she could write something to share with a child. Nicole kindly accepted the challenge and, after several subsequent conversations also offered to write the essay below, for adults, which I share with you here.

The past two months have been harrowing and volatile for the world’s Jews, myself included. And while it feels like we are in unprecedented times, history tells us, that, in fact, there are countless precedents and we would be wise to understand our history so we can navigate the future with a greater understanding of what may lie ahead.

I am grateful to Nicole for sharing her time and her extensive knowledge so generously with my family and with all of you. This is one of the longest pieces we have published, and certainly the most scholarly. I think it adds much value to the cannon.

Happy Chanukah to all who celebrate!

Natalya

I am a literary scholar of the Middle Ages.

October 7 and the ensuing responses from the left have crystalized for me the intimate connection between the medieval antisemitism I studied and the progressive antisemitism I witnessed in my own life.

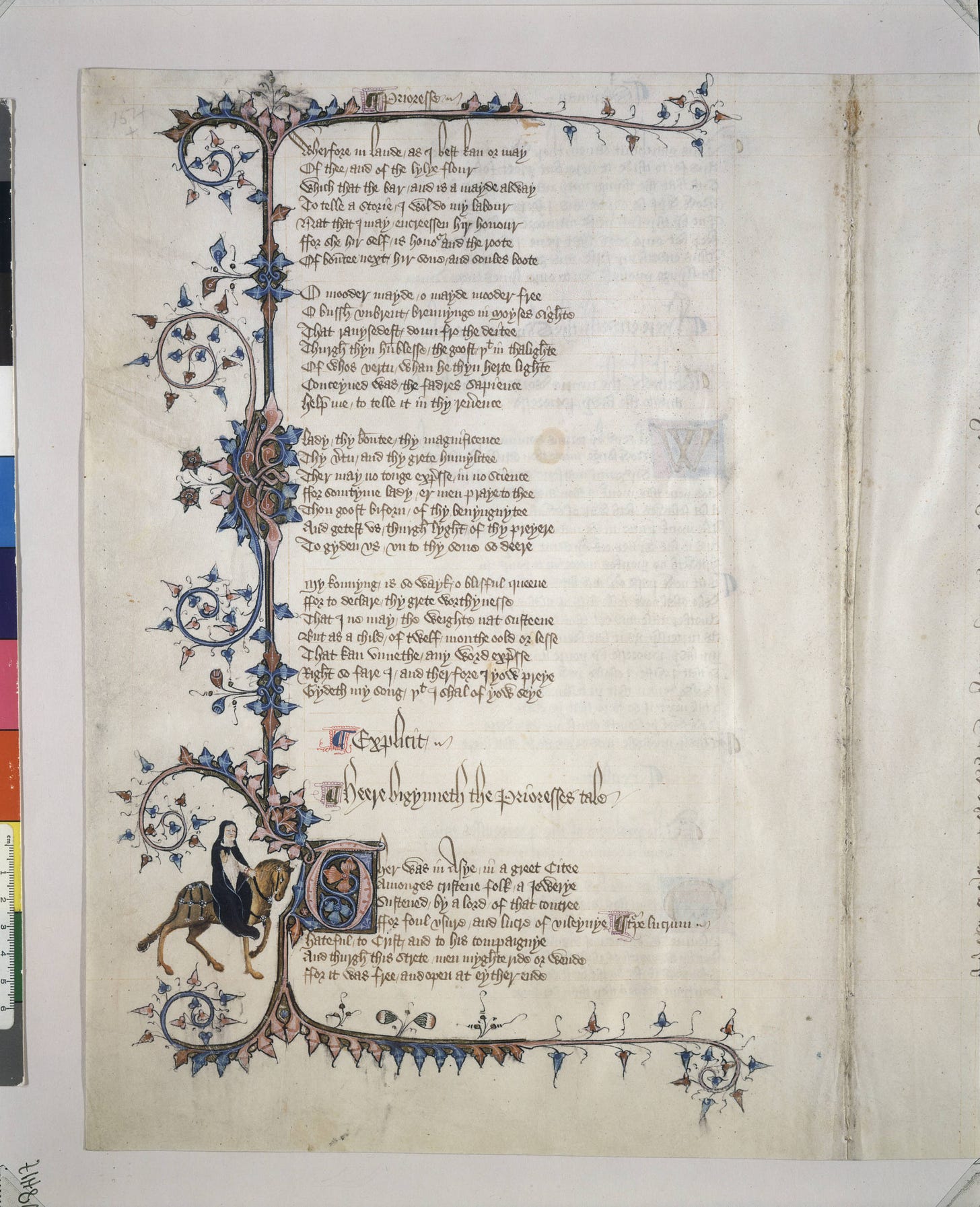

With torment and with shameful deeth echon,

This provost dooth thise Jewes for to sterve

That of this mordre wiste, and that anon.

He nolde no swich cursednesse observe.

"Yvele shal have that yvele wol deserve";

Therfore with wilde hors he dide hem drawe,

And after that he heng hem by the lawe. 628-34

(With torment and with shameful death for each one,

This magistrate had these Jews put to death

Who knew of this murder, and that immediately.

He would not tolerate any such cursedness.

"Evil shall have what evil will deserve";

Therefore with wild horses he had them torn apart,

And after that he hanged them by the law.)

Chaucer, Prioress’s Tale, Canterbury Tales, late 1300s

“Evil shall have what evil will deserve.”

Who says that about civilians murdered in a conflict? About elderly people? About babies? About children and young people?

Chaucer’s Prioress said it without shame about Jews at the end of the fourteenth century, her words passed down as part of the Canterbury Tales, one of the most celebrated poems in English literature. A young Christian boy had died – an innocent murdered by Jews. Therefore, all the Jews had to die.

“He would not tolerate any such cursedness.”

The story belongs to a popular medieval genre known as “miracles of the Virgin Mary” which was often rabidly antisemitic. A little Christian boy walks through the Jewish ghetto of an unnamed “great city” in Asia every day on his way to school, singing a Christian prayer to the Holy Virgin. The Jews murder him for his piety and throw his body in a privy, where it is discovered by his mother. After he is found, the child begins to sing, in spite of having had his throat cut.

It turns out the Holy Virgin has placed a grain on his tongue which allows his miraculous song.

One of the most remarkable things about this tale is that its brutal antisemitism is only a side plot, the murder of an entire community meriting only a few lines in a tale whose main focus is the miracle of the Holy Virgin. To give you an idea of how well accepted antisemitism of even the most violent type has been, historically, in the West: for most of this tale’s critical history before the Holocaust, most readers did not even remark upon the fact that it features a mass murder of Jewish people.

Over the past two months, I have been thinking a lot about the Prioress’s Tale, particularly about the idea of the corpse that sits up and speaks.

For fifteen years I taught this tale in college classrooms and believed myself to be teaching history.

Since Oct. 7 I have been shocked to discover that the Prioress’s mentality is not dead at all. Like the little boy in her tale, it is sitting up and singing its terrible song right now.

—

Since October 7, I have watched a sizable portion of the progressive left, many of them young people, evince an attitude to Jews that is not at all far from that of Chaucer’s Prioress.

The logic of modern progressive activists is very similar: innocents have been harmed; some Jews have been involved in their harm; therefore, all Jews deserve to die. This is the mentality that instructs the ripping down of posters of kidnapped Jews on city streets, that instructs the Chicago chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America to decorate their social media with images of paragliders, that instructs the gleeful celebration of Oct. 7 by progressive feminists even as video footage emerged of a young woman murdered by Hamas being driven through the streets of Gaza half-naked in a pick up truck for people to spit on, that justifies high school students rioting because a teacher dared to express public support for Israel.

“Evil shall have what evil will deserve.”

“He would not tolerate any such cursedness.”

The fact that the most virulent expressions of antisemitism since Oct. 7 have been seen in those under the age of thirty indicates a serious flaw in our education system. We need to acknowledge that the power of the Holocaust as an educational tool (always a flawed at the best of times) is now extinct.

As the journalist Liz Highleyman has remarked, there has been a generational shift in understandings of the Holocaust (Highleyman). Those of the Generation X era were born as little as twenty years after the Holocaust. It was close to us. We knew survivors.

But this is no longer the case for young activists today. A college freshman in 2023 was born 60 years after the concentration camps were liberated.

We can no longer count on the power of historic proximity to guard against antisemitism. We need to be more systematic in our understanding of antisemitism, reaching deeper and farther back into Western history. We need to be more analytic, helping the new generations to understand the exact nature of the millennia-long prejudices against this tiny religious minority (less than 2.4% of American adults are Jewish).

If we are to avoid violent pogroms in the twenty-first century, we need to know the fourteenth century much better.

Amazingly, for a group typically so sensitive to racial and ethnic power dynamics, the left has not responded to the emergence of antisemitism in its ranks with any soul searching or self-examination. The assumption among progressives seems to be that because they are antiracists in other ways, antisemitism could not possibly live in their community.

The left is anti-fascist and hates Nazis, the argument goes, therefore they cannot be antisemitic. The left cares for the downtrodden, therefore they cannot hate Jews.

But as the Prioress’s Tale reveals to us, this is not how antisemitism works. The Prioress is an advocate for the marginalized. Her tale is about the sufferings of a little boy and a poor widow. In her portrait in the Canterbury Tales “General Prologue” Chaucer describes her as a pretty young nun with excellent table manners and a heart “so charitable and so pious” (143) that she would weep at the sight of a mouse in a trap. The person who coolly describes the murder of an entire neighborhood is also someone who feeds her dogs on bread and milk and cries if anyone hits them with a stick (149).

Historically and today, antisemitism pairs quite easily with a care for the downtrodden. Progressive politics is no protection against it and actually might function as a risk factor for its development. I say I have been shocked by the events of the past few weeks but I really should not have been. Even before I became a medievalist and encountered the long pedigree of Western antisemitism, I witnessed the combination of antisemitism with a progressive commitment to social justice in my own life.

I grew up in an anti-colonialist family, proud of our Irish heritage and our role in the overthrow of British occupation. I had a close family member who regarded themselves as a staunch defender of human rights. This person saw the struggles of the Irish reflected in those of the Palestinians and was strongly critical of Israeli policies. They were also an antisemite who believed that Jews were manipulative and inhumane, looking out only for their own interests. I remember being told, at the age of 10, not to befriend a little girl across the street because she was Jewish.

As I would do later with the antisemitism of the Prioress, I wrote off my relative’s antisemitism as “history.” This relative was a generation older than me. There was no way, I thought, that young people could ever hold these views.

It was all going to go away.

Looking back, I know my approach was influenced by how I had been taught about the Holocaust.

As a young person, I remember having the Holocaust presented to me in school (and also in movies and popular culture) as a singular event originated by the Nazis. We did not learn about the history of Western antisemitism. We learned that the Nazis were bad, that they committed horrible crimes against the Jews, and that as long as we were anti-Nazi and anti-fascist, the Holocaust would never happen again.

My education was not only historically limited, it was also lacking in analysis. We weren’t taught the characteristics of antisemitism or how to identify it. We did not learn its long history in the West or its unique character. As a college teacher, I know that subsequent generations also received this same education. Always, my college students were surprised to learn of medieval antisemitism during study of the Prioress’s Tale.

“I can’t believe it’s been going on for so long!” was a common remark among students upon reading this tale.

Understanding not only the duration but also the nature of Western antisemitism is more important now than it has ever been. When we understand the nature of antisemitism, we understand why the current American left is so vulnerable to its power – and so incapable of detecting it.

Whereas the predominant racist ideology relating to black and colonized peoples has centered on their being animalistic and primitive, in need of “civilized” control, the primary characteristics of antisemitism are of the Jew as wily, conniving, and powerful – an oppressor in his or her own right.

This long cultural tradition means that it is very easy for young people having a conscientious objection to some of the politics of Israel, just as they might of any other sovereign nation, to flow straight into antisemitic notions of all Jews as oppressors and killers.

The idea of the Jew as a wily oppressor originates in the Gospel of Matthew, which claims that, when asked by the Roman governor Pontius Pilate, the Jews gave up Christ to be crucified (Matthew 27: 24-26). As a result, Western Christians regarded the Jews as murderers of Christ. The Christian thinker Bernard of Clairvaux, writing in the twelfth century, characterized Jews as criminals, permitted to live in Christian lands as a spur to Christian piety: “The Jews are for us the living words of Scripture. They are dispersed all over the world so that by expiating their crime they may be everywhere the living witness of our redemption...” (Clairvaux 462)

The Jews’ status as Christ killers gave birth to other racist fantasies of Jewish oppression in the Middle Ages. The legend of the “Blood Libel,” alleged that Jews were killing Christian children in order to satisfy their supposed need for "Christian blood" in making matzah or for use in other Passover rituals. While Church authorities often opposed such stories, the myths lived on in popular belief, sparking a number of massacres of Jews in Western Europe (Nirenberg).

The medieval fear of Jewish people meant that Jews were afflicted with murder, harassment and forced exile throughout the Middle Ages. In the First Crusade of 1096, European Christians on the way to take Jerusalem from the Muslims massacred Jewish communities along the Rhine and Danube. Crusaders justified their murders on the basis that it was no use seeking out an infidel in the Holy Land when they had the “killers of Christ” living among them (Chazan, 55-60).

This same idea also motivated the murder of seventeen people, six of them children, whose bodies were discovered in 2004 at the bottom of a well in Norwich, UK. Dated to the twelfth century, the bones were later subjected to DNA analysis which revealed them to be of Ashkenazi Jewish heritage, making them likely victims of an antisemitic massacre recorded in 1190 by the chronicler Ralph de Diceto, who wrote that “Many of those who were hastening to Jerusalem determined first to rise against the Jews before they invaded the Saracens. Accordingly on 6 February all the Jews who were found in their own houses at Norwich were butchered” (Davis).

A century after the Norwich massacre, Christian fears about the Blood Libel justified King Edward the First’s Edict of Expulsion, which banished the Jews from England (they did not return until the mid-seventeenth century).

In the fourteenth century, the arrival of the Black Death prompted new outbreaks of antisemitic violence. Many blamed Jews for the disease. An estimated 300 Jewish communities were attacked, and thousands of Jews were murdered by Christians who believed that the Jews were causing the plague by poisoning wells (Gottfried, 73-75).

Ironically, the two forms of Western racism that are now being split down the middle of the American political spectrum were united in the Middle Ages. Both the Muslim and the Jew were regarded as devilish threats to the civilization once known as “Western Christendom.” As the above examples illustrate, crusaders headed out to kill Muslims in the Holy Land regarded the murder of Jews as a perfect prelude to that activity.

In the landscape of our current political discourse, the issue of antisemitism has been very confusedly wound up with criticisms of Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians and about the Netanyahu government’s military actions in Gaza.

Rabbi Daniel Bogard, himself a progressive and a critic of the Netanyahu government, has noted the antisemitism inherent in a disproportionate concern among leftists over the actions of Israel as compared to other nations.

Criticisms of Israel may be justified, Bogard notes, but placed in the context of a silence over other human rights violations, they take on an antisemitic character: “Obsessive focus on Israel; deeply disproportionate framing of Israel’s crimes compared to any other nation-state (e.g. Russia, the U.S., Morocco, China, Syria, Egypt etc); intensive critiques of American Jews and framings about our power.” (Bogard)

Having seen the many blatant expressions of antisemitism on the left, most particularly among young leftists, in recent weeks, we cannot deny the power and the durability of antisemitism in the West. Having seen, too, how quickly this antisemitism descends into violence and abuse, we cannot deny the danger of allowing the hatred for a tiny religious minority to continue unchecked.

Follow Nicole on X at @NicoleSidh44337

References

Bernard of Clairvaux, Epistola 391, trans. Bruno James. The Letters of St. Bernard of Clairvaux. London: Burns Oates, 1953.

Bogard, Daniel. “Critiques of Israel can be both true *and* antisemitic…” X (formerly Twitter), 8 Nov., 2023. https://x.com/ravbogard/status/1722258776009666865?s=46&t=OuOWukuM6jw8tKG_2BniAA

Chaucer, Geoffrey. The Prioress’s Tale, Canterbury Tales. 7.3 The Prioress' Prologue and Tale | Harvard's Geoffrey Chaucer Website

Chazan, Robert.. European Jewry and the First Crusade. Berkeley: U. of California Press, 1996.

Davis, Nicola. “Jewish Remains Found in Norwich Well Were Jewish Pogrom Victims – Study” The Guardian, 30 August, 2022. Jewish remains found in Norwich well were medieval pogrom – study | Archaeology | The Guardian

Gottfried, Robert S. The Black Death: Natural and Human Disaster in Medieval Europe. New York: The Free Press, 1983.

Highleyman, Liz. “I think I can understand this generational disconnect…” X (formerly Twitter), 25 Oct. 2023, 10:40pm, https://x.com/lizhighleyman/status/1717370685146935611

Nirenberg, David. “The Impresarios of Trent: the long and frightening history of the Blood Libel.” The Nation, Nov. 16, 2020.The Long and Terrifying History of the Blood Libel | The Nation