About that new Boston mask study in the NEJM...

Another example of bad science from the public health community

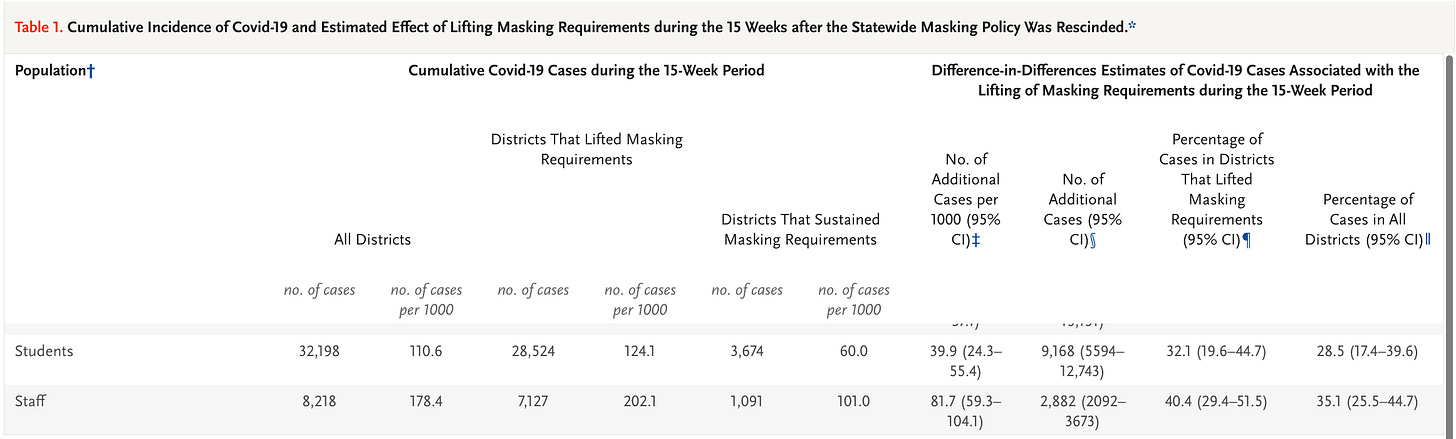

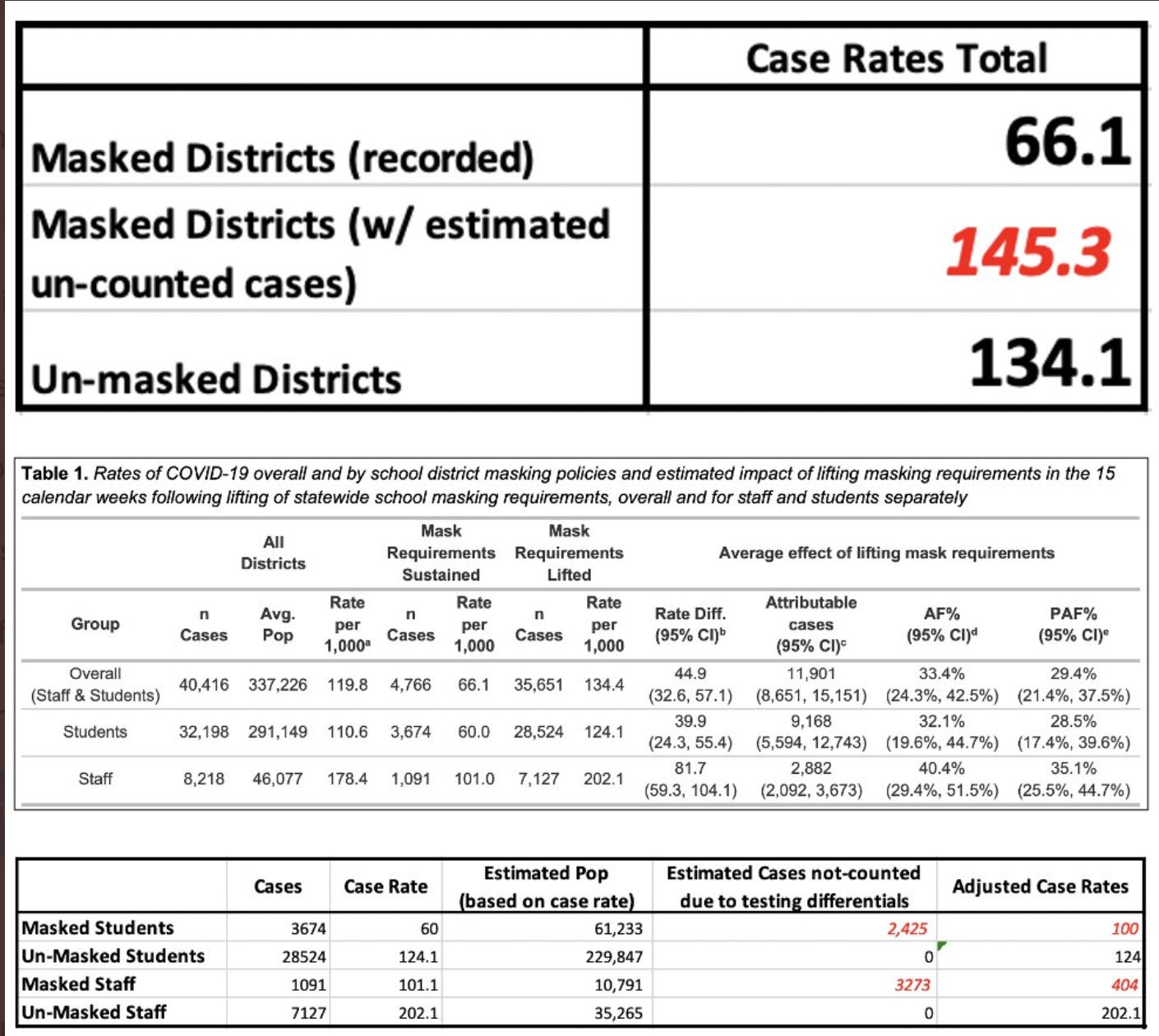

The New England Journal of Medicine just released a new mask study comparing Boston and Chelsea school districts—which remained masked until June of 2022—to the several other Massachusetts school districts. It claimed that the districts that remained masked reduced transmission by ~45%, from a case rate of ~ 110, down to 60 for students, and 178, down to 101 for staff.

Unfortunately, the study is rife with potential methodological flaws. This is an observational study, which means it is incapable of ascribing cause. This is because observations can be heavily confounded. Let’s look at the most obvious confounder, testing.

The authors acknowledge that they do not have testing data for the different districts.

The importance of this cannot be over-stated.

Testing rates matter hugely—test more, find more cases. It’s just how it works. If you don’t have a testing baseline, you don’t have a baseline at all. Back in August of 2021, the CDC specifically exempted masked contacts from contact-tracing. It was, in fact, their most valuable weapon in the war to keep kids masked. This is because schools (and parents) were told, if both kids are masked, then even if one tests positive, the other masked child is not considered a close contact, and so does not have to be quarantined at home. Few administrators were able to resist.

The authors note that the “test-to-stay” program—which included contact tracing that excluded masked contacts from being defined as close contacts—was made optional in January 2022. They state that too few schools chose to maintain test-to-stay to make a difference.

However, there are several issues with that statement. First of all, we see from the slide below, that rather than removing the “test-to-stay” program, it simply made it optional. Schools were able to continue doing the “test-to-stay” program. So what you actually see here, is two totally different testing options that could be chosen.

Excerpt: MA DOE COVID Testing Guidance

In fact, this may account for nearly all of the differences. Let’s look at the changes. The authors provide a slide of all the school districts that lifted mask mandates that also opted out of the “test-to-stay” program. That chart is shown below. They do not provide a similar chart for the masked schools that chose the other option, i.e., to continue with pooled testing and “test-to-stay”. I presume this is likely because most of the schools that maintained mask mandates continued using the “test-to-stay” program.

If that is the case, what we are looking at is two totally different testing modalities being applied by the two groups. Seeing that the “did not lift” group is the one with the highest pooled testing rate, and that the variation increased after the mask mandates were lifted, that seems like exactly what we are looking at.

Beyond this, GBH news reported that in April opt-ins in Boston Public Schools for pooled testing were running at just 22% of students.

We simply have to have a testing baseline and the same testing modalities to even begin to compare.

The authors note that “test-to-stay” and was abandoned by most of the unmasked districts. Contact tracing was also abandoned at that point in those districts. However, what this ignores, is the kind of testing these unmasked districts were doing.

When school districts opted out of “test-to-stay” they had to opt in to weekly antigen testing. The authors note that most of the unmasked districts opted out of “test-to-stay” and in to weekly antigen testing. This means that every one of these districts was asking their students and staff to administer twice-weekly at-home rapid antigen tests, and then to report them to the school—effectively catching every single positive case for those who opted in. If they tested positive, while the close contacts weren’t required to quarantine, the person who tested positive was.

Let’s contrast that with the schools that elected to keep masks, and “test-to-stay”. Again, the authors don’t tell us if the school districts that didn’t lift their mandates continued with the “test-to-stay” option, but the much higher level of pooled testing (which was the backbone of the “test-to-stay” program), and the authors not including that information in the supplement, suggests that in fact it was the case. Any school that elected to continue “test-to-stay” and masking was still required to perform contact tracing. However, any contact tracing would still, per CDC guidelines, exempt any contacts where the interaction was between two masked people. Thus, while students in schools who dropped mask mandates were testing twice per week, effectively catching every case, in schools that continued “test-to-stay,” masked close contacts would not be asked to test, even if they had been in the the presence of a positive case.

Is it possible to estimate how many cases might have been missed due to this difference in testing? Yes, it is. This is because, quite a while ago, the CDC published an MMWR with contact tracing information on a completely masked school. In this study, we see that the number of secondary cases that arose from each of these masked children was 0.66 additional cases. Each masked teacher generated an average of 3 additional cases.

We can take the existing case rates, and cases and extrapolate the population of all of these groups. From there, we can use these estimates to see how many cases might have been missed, due to the suppression of masked cases, due to the close contact definition. The results are below. Using this estimate of additional cases, the masked districts would have missed, somewhere around 5700 additional cases—which would bring the case rates largely in-line with the unmasked districts.

The next logical question is, what were the case rates in the community for each of the districts? In fact, we can see that they were largely similar, with some slight differences, and with the surrounding town of the masked districts on the higher level amongst the three groups. This is quite consistent with the estimate above.

Again, we don’t have the testing protocols for either, but the fact that there were two options, and that there seems to be a bifurcation in pooled testing, suggests that the masked and unmasked groups used largely different testing modalities.

Indeed, one of the authors seems to suggest this in one of her rebuttals to questions raised when the article was brought out for pre-print.

This is the ultimate logical fallacy. Children and teachers missed school not because they were sick, but because of testing practices designed to catch every single case—even if asymptomatic—and then required those cases to miss a certain number of days in quarantine. The other test-to-stay, coupled with masks allowed those districts not to “find” cases in masked students and staff, thereby allowing them not to miss school—but seemingly having no impact on transmission.

Several months back, we did an analysis of masked, and unmasked districts across the 500 largest districts to see if masking did indeed reduce days missed. It turned out that the opposite was true. In fact, masked districts missed approximately 4x the amount of school as unmasked districts.

Why did masked districts miss more school? We don’t really know, but I suspect it comes down to control. Districts that masked also tested more. They also were more likely to have more draconian isolation policies. Districts that didn’t mask less so. This is borne out in the data. What we see in the data is that masked districts do have higher case rates, which would be expected both from their testing practices, and their seasonal patterns—nearly 2.5x higher during the January peak. But kids in masked districts missed nearly 4x more school than unmasked, meaning that the choices employed around forced quarantine were much higher even than the difference in the case rate.

Like so many other mask studies, you could drive a truck through the holes in this mask study.

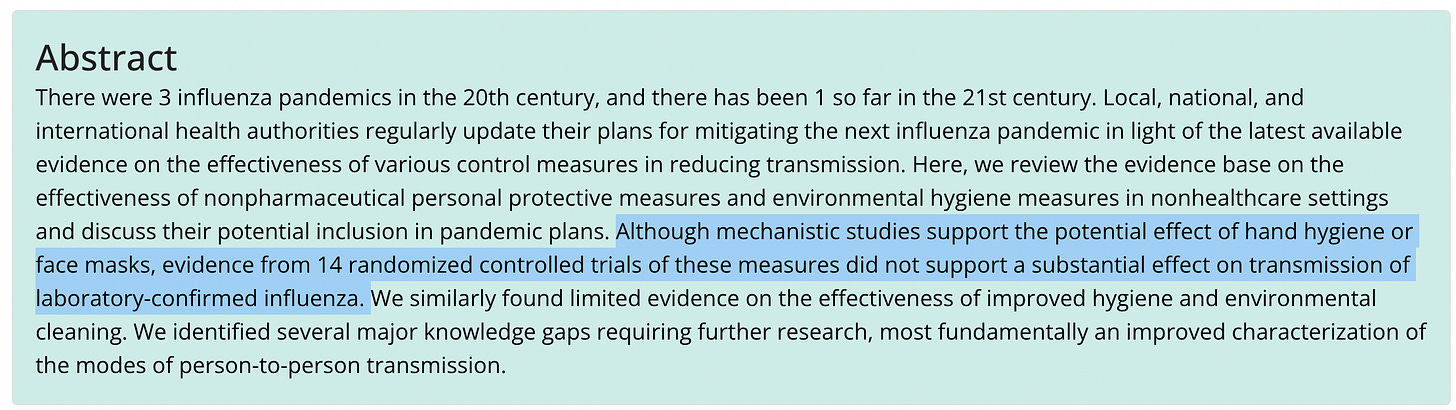

Way back in May of 2020, the CDC did a systemic review of all extant randomized controlled trials of masks and other mitigations. They found no impact. Given this, they noted an urgent need to better understand transmission of respiratory illnesses. Instead of doing that work, and conducting real, randomized controlled trials of mask efficacy, the CDC and public health community continues to churn out one bad piece of science after another to justify their policies.